Over the course of a road trip across America, I was lucky enough to spend plenty of interstate time with my friend Andrea Armeni. One of the things we discussed at length was the question of in what circumstances the search for culinary authenticity turns farcical.

Florence Fabricant, in a recent article, embodies a common attitude amongst American food writers when she reveals the results of an exhaustive search for the true recipe for bucatini all’amatriciana, one of Italy’s most beloved pasta dishes: “After half a dozen plates of it during a recent trip to Italy, one detail became clear: for any pasta all’amatriciana to be authentic, it must be made with guanciale—cured, unsmoked pig jowl.”

Florence Fabricant, in a recent article, embodies a common attitude amongst American food writers when she reveals the results of an exhaustive search for the true recipe for bucatini all’amatriciana, one of Italy’s most beloved pasta dishes: “After half a dozen plates of it during a recent trip to Italy, one detail became clear: for any pasta all’amatriciana to be authentic, it must be made with guanciale—cured, unsmoked pig jowl.”

Although it would be a difficult hypothesis to test empirically, Andrea and I had the same immediate reaction to this statement—his from growing up in Italy, mine from living there for a while: in Italy, almost nobody would care in the least bit whether pasta all’amatriciana were “authentic.” People would care whether it tasted good.

Now, just because people in Italy wouldn’t care whether amatriciana were authentic doesn’t mean we shouldn’t. The preservation of culinary history, lest old recipes be lost in time, is a noble endeavor. But historical documentation doesn’t seem to be the purpose of the food writers who go around enforcing amatriciana’s authenticity. It’s more the idea that there’s one, and only one, way to make this dish—a blend of I’ve-been-there-and-you-haven’t self-righteousness with cultural/culinary naïveté.

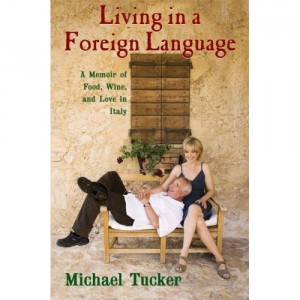

To wit: “Italians take guanciale for granted, but it’s fairly new to American kitchens. Almost all the recipes in American cookbooks,” continues Fabricant, “call for ordinary bacon—which is too smoky—or Italian pancetta, which is too lean…‘Good guanciale makes all the difference,’ said the actor Michael Tucker, an accomplished cook, who, with his wife, the actress Jill Eikenberry, has a house in Umbria. In his book, ‘Living in a Foreign Language’ (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007), he describes buying guanciale from Ugo Mazzoli, the butcher in Campello sul Clitunno, near his house.”

To wit: “Italians take guanciale for granted, but it’s fairly new to American kitchens. Almost all the recipes in American cookbooks,” continues Fabricant, “call for ordinary bacon—which is too smoky—or Italian pancetta, which is too lean…‘Good guanciale makes all the difference,’ said the actor Michael Tucker, an accomplished cook, who, with his wife, the actress Jill Eikenberry, has a house in Umbria. In his book, ‘Living in a Foreign Language’ (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007), he describes buying guanciale from Ugo Mazzoli, the butcher in Campello sul Clitunno, near his house.”

Guanciale is lovely in amatriciana; few would dispute that. But Simone, the Genoese guy who taught me to make amatriciana, does it with pancetta—like his mother did. Would Simone love a well-made amatriciana with smoky American bacon, too? Of course he would. He’s not a lever-pulling lab rat. He’s just a dude who, like many other Italians, likes good food.

Is amatriciana made with guanciale? Yes.

Is it made with pancetta? Yes.

Is it made with Tyrolean speck? With French lardons? Probably, somewhere in Italy, yes.

To illustrate the absurdity of Fabricant’s point of view, Andrea offers the following hypothetical: imagine an Italian food critic undertaking a careful investigative journey through the American pastoral hinterland in search of the authentic hamburger. She tries a half-dozen burgers, reads a few cookbooks, and concludes, in her article in Corriere della Sera, that “for a hamburger to be authentically American, it must be made only with Wisconsin cheddar cheese, lettuce, and tomato, and it must be served with french fries.”

Fabricant is not wrong, exactly, about how to make a good plate of bucatini. But she, like too many food writers, constructs a counterfactual Italy of culinary dogmatism, a population of finger-wagging guanciale zealots, a nation full of Ugo Mazzolis harrumphing around about how the world is going to shit now that people are making amatriciana with pancetta.

People and recipes aren’t anthropological tokens. They’re living things, the products of neural assemblies and proteins and chemicals bouncing across the ages. Narrow your gaze and squint your eyes too tightly in the search for authenticity, and you might miss that whole, beautiful landscape.

Fulmer

Great perspective for those of us who get caught up in the gastro-ontological search. Quality vs. authenticity. I have been guitly of getting lost in the minutiae of culinary nostalgia. Earlier this year in a mole cooking class we discussed the many facets, merits and authenticity of mole in Texas as well as elsewhere. I found the recipe I enjoyed most was not exactly “According to Hoyle”, but it was so satisfying. To paraphrase that which you expressed so well, “Getting lost in the trees we sometimes miss the forest”.

Kent Wang

Salumeria Biellese, based in New York, makes a good gunciale, available at Central Market, and I imagine many places in New York.

juan ciale

i very much enjoyed this entry. i am wondering whether you have given any thought, from a cognitive standpoint, to the effect of such “culinary dogmatism,” as you artfully put it.

does it enhance the pleasure, on the occasions in which you can match an outstanding taste with hitting a marker for authenticity, or does it rather detract from the pleasure of, say, a perfectly delicious amatriciana, because one gets caught up in the pancetta faux-pas?

my intuition suggests that the latter occurs, by and large, on the basis of some version of cognitive dissonance – some instance of (1) “ooh, i am enjoying this” and (2) “ooh, i ought not to be enjoying this as much as the authentic version”.

Mark Ryan

Equally (if not more important) than the particular fatty pork product used is the quality of the tomatoes and the pasta. Foodies (myself included) can often get caught up in the hunt for a particular item and then overlook the foundations of a dish.

g

Being taught Amatriciana by a Genoese, is like being taught Sashimi by a Swiss. And I am Genoese, from a Genoese family.

The only reason Italians outside the center do not obsess over guanciale, is because guanciale is not available. The same reason why people outside Liguria do not obsess over the right basil when they prepare pesto, and so on…

Can there be a good amatriciana-like pasta made with bacon? Yes, I spent many years outside italy perfecting my recipe. Am I happy as a baby when I have access to guanciale? Yes

Paige Flores

i love Italian Food specially those juicy pastas. They are really delicious.;~;

Maryface

How do you pronounce “jowl” bacon? Is it “jole”, “joel” as they say in Indiana? I suspect Indiana has a local mispronounciation. Help settle a family dispute. Thanks.