The relationship between tourists and the places that they like to go has been ambivalent since tourism—travel as entertainment—became a real global industry in the early 1900s. Sometimes cities become caricatures of themselves, molded into their own exaggerated and inauthentic images abroad. Other times, they just become ugly high-rise beach resorts or overcrowded, overpriced wastelands.

But then there are some places where something completely different happens—where the intersection of tourists and locals has spun off, across the years, into something newer and stranger than could ever have been contemplated by either party to begin with.

To say that Amsterdam, where pot, mushrooms, and hallucinogenic substances of all sorts are legal, is only about the drugs would be to adopt a narrow perspective on the city. But Amsterdam is about the drugs, and one of the funniest things about the middle-aged American tourists that visit Amsterdam in droves, most for the first time, many with their children,

is that a lot of them seem to have had absolutely no clue what they were getting into.

They weren’t exactly lied to, these unsuspecting families. They were truthfully told—by the tourist board or the travel guide, perhaps—about the inescapable romance of the canals. And these canals, like the ones in Venice and Bruges, really are that romantic. In Amsterdam—unlike in Venice—you can get everywhere in a car or on a bike, and the bridges are so low, there’s little in the way of actual transport along the waterways, aside from the occasional floating dining room full of tourists. These boats, which can actually fit under the bridges, are like little pieces of a cruise ship that has just been flattened by the accidental foot of a giant.

The problem might really be that the middle-aged families spent too much time reading the travel guides. Amsterdam’s “stunning juxtaposition of old and new,” waxes Time Out Amsterdam—perhaps in an attempt to fit as many guidebook clichés into one sentence as possible—“still has to be seen to be believed.”

The travel writers rave on about Anne Frank, Van Dyck, Van Gogh, bicycles, tulips, windmills, wooden shoes; about how it’s so different but so European, the consummate stop along the Grand Tour; about the lovely (but not unsafe) lean of the old merchants’ houses on the Prinsengracht and the Herengracht; about the friendliness of the Dutch populace and the “impossibly welcoming corner cafés.”

It is that same publication, Time Out, that includes the most prominent guide to the coffeeshops—the places in Amsterdam where marijuana is sold legally—that is available on the mainstream commercial market. The section covers only four of the book’s more than 300 pages, but it is still an uncommon dose of realism among the major chains of travel guides, praising certain coffeeshops for their “wide range of imported grass,” or their “top-quality 80% organically grown weed.”

Perhaps purposefully or perhaps not, that section of Time Out Amsterdam is buried after Bars, before Shops and Services, and between pages 147 and 153 of a 316-page book. There is also a five-page essay entitled “Sex and Drugs” at the end of the “In context” section, after “History,” “Amsterdam Today,” “Art,” and “Architecture.” But we former travel writers know that this is the section of a travel guide that nobody ever reads.

Certainly my friend’s mother, a high-level executive at a multinational company, didn’t have time to read it. She, probably one of the most cosmopolitan 50-something women in the world, was shocked when she walked into a “coffeeshop,” asked for the menu, and was handed a list of ten kinds of marijuana with prices by the gram. How could it possibly be that nobody had ever told her?

Well, one of the interesting aspect of the decriminalization of marijuana and mushrooms in Amsterdam is that it happened in the late 1970s, after the hippie generation had pretty much grown up. So even if the executive wasn’t a reformed hippie, a lot of the reformed hippies themselves have no idea what they’re missing. A lot of them probably wouldn’t care anymore anyway, at least any more than intellectually.

Still, how could the drug culture of Amsterdam could be such a taboo subject among the media outlets that cover the city as if it is just another beautiful European capital? Travel writers, as a lot, are fairly observant—but who is writing these books?

As you navigate the city’s bewildering network of twisting, dead-end streets and gently bending canals, one of the first things that strikes you is how many of the offerings seem meant to be experienced—only meant to be experienced—under the influence of marijuana or mushrooms. There is a store that sells only holograms. There is a café with stalactites and stalagmites. There are restaurants with life-sized dolphins made from plaster, restaurants where you eat in the dark, restaurants where you eat on a La-Z-Boy, and what must be more than a thousand purveyors of Belgian fries with mayonnaise (the first time you try them stoned, you realize that even if the fries are for everybody, they’re most especially for the stoners). It is like an open network of sensory pleasures and communicative understandings built into the rest of the city that suddenly illuminates before your eyes at the moment that you get high.

Out of respect for my colleagues, I don’t want to believe that the travel writers haven’t actually visited the city. So my only explanation is that many of the writers have never actually tried the drugs, and thus don’t understand how deeply the drugs filter through the culture and how incomplete an account of Amsterdam really is that doesn’t talk a lot about them. (It never ceases to amaze me how much more often people who have never tried drugs like to talk about drugs than people who have tried drugs.)

In any case, this lack of information leads to a lot of strange moments of contact between culture and subculture, like the executive in the coffeeshop looking for a cup of coffee, or the lost British couple with the young child wandering into an alley of the red light district and getting directions to Amsterdam’s most famous tourist attraction from a heroin dealer to whom they’re later compelled to give an involuntarily large tip.

They’ll get there in the end. Like the fairytale castles of Bavaria, the Anne Frank House is one of the few educational tourist attractions in Europe that holds the interest of children. Her story is their story; it speaks to them. But it is one of the few places in the city where the two cultures of tourism—the chaste and the profane—do not collide. Maybe there is something decadent and disturbing about visiting a monument to the Holocaust under the influence of a mind-altering substance.

There must be something right about that. Or, at least, I feel it too, even if it’s just an American cultural norm—the idea that the choice to smoke pot is a selfish one, or the idea that pot cannot be used to enhance other things in our lives, especially not emotional and serious ones—sex, for instance, or mourning. Even the college kids seem to sober up to pay their respects to Anne Frank.

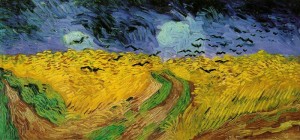

It is quite a different story at the Van Gogh museum, a space that carefully straddles the intersection of the two cultures—conventional and altered states of mind. For Van Gogh, of all people, to have come from Amsterdam is almost too perfect to be true. The fight between conventional and altered states of mind is something that the painter himself frequently confronted—first with absinthe, and later with depression and epilepsy.

Could the form that these paintings’ immortalization takes possibly be any more appropriate to the artist? In front of “Wheat Field with Crows,” you might see a stuffy German couple with a deep knowledge of post-Impressionist history next to two American college girls that are truly, madly, and deeply high for the first time in their lives. And all four of them, each extracting his or her own experiences of color and categories of meaning, can barely handle how fucking good the painting is.

Those are the castles of Bavaria for a young adult. There is education the emotional way, the reason for the Van Gogh poster on the dorm room wall. But these kids’ experience in Amsterdam is also inescapably about America. Because one of the most curious, if understandable, aspects of the drug culture in the city is the extent to which if it’s legal at home, it’s not worth trying.

There is one store in the old city center that sells probably five hundred kinds of psychoactive and physiologically active substances—from a package of dried and shredded wormwood, the active ingredient in absinthe, to a potted San Pedro cactus, which makes you trip for eighteen hours and grows only in the area around Vilcabamba, Ecuador’s Valley of Eternal Youth. What is the question that the clerks hear most at this store? “How safe is this?” “Are you sure I won’t flip out?” “How much does this cost?”

No: “Is this legal in the USA?”

If it is, they’re not interested. You hear it more often from the Americans, and the younger they are, the more you hear it: There might be nothing that damns the approach taken by Reagan’s War on Drugs and its progeny more visually, more empirically, than to watch a steady parade of America’s youth combing this little store for something—anything—that they’re not allowed to eat at home. And that too is part of what Amsterdam is about. Their drug subculture is very much about us.

The Dutch really went out on a limb when they made this courageous choice in the late 1970s. However you feel about it, you have to admit that legalization was pretty ballsy. So what did they do to deserve the US drug tourists? Us? And now that they have us, what can they do with us? The problem for all the visiting pot smokers—American or otherwise—who arrive hoping to have some cultural contact with a city that is indisputably an object lesson in tolerance is that in Amsterdam, unlike in other Dutch cities, they, the visitors, make up most of the customers in most of the coffeeshops.

That is no trivial matter. Because if you came to Amsterdam to smoke pot, you immediately realize that for the Dutch people it’s just something else to do, like drinking wine with dinner, not some holy grail of open-mindedness. In the US, you feel like one of the cool kids for smoking pot. In Amsterdam, you’re one of the losers, at least in the eyes of the locals (and for me, at least, those are the eyes that matter when you travel, however condescending they might be). It’s hard, thus, once you’re in Amsterdam, to distance yourself from your fellow smokers or to think of yourself as anything other than a drug tourist. And so you accept your place in the city’s moral hierarchy.

That said, there’s a lot more sketchy shit going on in the city than whatever’s happening in the coffeeshops, and the locals’ reaction is eminently understandable when you look at what else the pot and mushrooms attract like magnets. But when people point to Amsterdam and say, look at all the druggies on the street, this is what would happen if we legalized pot, what they’re missing is that this is only what would happen if we legalized pot in just one country. The casual pot smokers might or might not come for the pot, but the people were really into pot would flock there from all over the world to the best city in that country, and they would create such a strong subculture there that it would come to envelop much of the city’s social life. And that’s what happened.

The locals, and the critics, are right that Amsterdam is now full of drug addicts. And they’re basically right that nobody wants to live in a city full of drug addicts. The pot smokers certainly don’t want to live in a city of drug addicts; most pot smokers are not drug addicts, and what a buzz kill it is to have your ephemeral mental state ruined by an angry guy shooting up in an alley. Not even the drug addicts probably want to live in a city full of drug addicts. But there are certainly a lot of true drug addicts among the people who think it’s worth traveling all the way to Amsterdam where strong hydroponic weed and peyote and mushrooms are sold legally and cheaply, over the counter.

And so among the people in Amsterdam who abuse drugs, very few of them are Dutch. You can say this is a failure for the city itself, but you can also say that the Dutch experiment is a success: Dutch levels of hard drug abuse and addiction are low by international standards. And if you’re constructing a behavioral economics argument about whether or not drugs should be legal in other places, that’s the only thing that should matter, because if everyone legalized pot and mushrooms, the drug tourists wouldn’t have to come to Amsterdam anymore, and it would become a lot more like the city the locals want it to be. We owe it to Amsterdam to be courageous too.

In the meantime, though, it’s a curiosity, and I love a good curiosity. Because even among the aspects of life in Amsterdam that do not clearly or directly derive from the drug culture, there is always the vague sense that they might, and that’s what makes it all so curious. The thing that separates the city’s famed red light district from others around the world is how visual it is. This is not just, it is not even mainly, a marketplace for sex. It is a show, women displaying themselves with bravado, sometimes playful, other times heartbreaking, for an audience so varied that it even includes, from time to time, the British family with the little child, lost on the way to the Anne Frank museum. In any other city, the little kid wouldn’t even know that he was in the red light district. And the red light district, and Amsterdam, is very much about those interactions too.

Perhaps this is part of why nowhere in town—not even its red light district—is there anything truly seedy or truly scary. It feels more like yet another urban thing that is, like the Van Gogh Museum, just designed to be seen—and perhaps this one is even designed while under, or designed to be seen under, the influence of something. Only, one might argue, a city planner in the intense visual depths of a mushroom trip would think to decorate a red-light district by illuminating its prostitutes (and the beds and sink in the background of their rooms) with real red lights that reflect off the canals and iterate beneath troupes of tourists whose moods span every possible point on the axis between sensory detatchment and urgent genital need.

The omnipotent haze of the drug culture, though, also has its subtler forms, and these are some of the most memorable. At some point, the question of whether or not the experience is about the drugs melts away, and the collective memory of your time in Amsterdam melts into one long trip: travel as escapist entertainment. One day my friends and I were meandering between an out-of-the-way coffeeshop and a third-floor pancake house, and we noticed rows and rows of people stopped along the sidewalks around the bicycle fisherman in the secondary canal below. We, too, stopped to watch.

The bicycle fisherman was a waterproof man, dressed from head to toe in municipal orange, sitting atop a long trawler that glided along the still water at an almost imperceptibly slow speed. He looked calm, practically sleepy, as he reclined in a spinning chair in the winter sun, his hand on the classic joystick of heavy machinery, lowering the forklift into the water and retrieving some of the hundreds of bicycles that sat at the bottom of the shallow canals. Every dip of the tongs into the mess of olive goo that flows beneath the city’s gently arching bridges would yield four or five partially crushed bikes and toss them into the heap of others, like a junkyard growing in the middle of the long boat.

Are these just the realities of living in a city of canals? Do that many people really throw their bikes, or ride their bikes, into the water? Or was the bicycle fishing a show by the stoners and for the stoners, a work of interactive performance art in which the city’s department of public works was involuntarily chosen to play the lead role?

Or did we just imagine it all?

Amanda Jones

Those bikes are all stolen. People steal them, use them for a day or two or however long, then pitch them in and I guess just steal another one. Anyway that’s what somebody told me.

This was a great piece. Hope you’re doing well. acj

Scott

It’s really one of the great cities of the world. As beautiful as Paris with far fewer tourists. All sorts of weird juxtapositions, prostitutes operating across the alley from a medieval church. Great post.

Peter

Fantastic review – I have been the boy lost in the Red Light District as a child following his father, and later I was the graduate that went largely to smoke pot and sit in coffee shops, playing chess. The city seems much better suited for the latter.

Den Haag escort

the drugs are not the problem, the real problem is the people ho bring them on the market.